Management tools are a dime a dozen. And yet, contrary to popular belief, most of them are good and helpful if used correctly and in an adequately defined context.

In “Tool Box Talks” we introduce you to common and less well-known tools and show you how you can exploit their potential for your enterprise, with today’s focus on the risk register.

What is a risk register and when should it be used?

The risk register is a risk management tool. Depending on the focus of the risk management activities, it documents risks related to a product, a project, a department or an entire enterprise. Though the tool stays the same for each of the perspectives mentioned, we strongly recommend having one independent risk register per perspective to avoid misinterpretation of the documented information (see “Do risk evaluations lead to faulty decisions?”).

A risk register should be used whenever risks need to be documented. The format of the risk register varies, depending on to the needs of the situation. An ad-hoc analysis, for example, generally requires less background information to be documented to be helpful than is needed for an extensive risk evaluation accompanying a complex and long running project. This difference in scope is reflected in the extent of the risk register. Besides the scope, the maturity of an organisation impacts the appearance of a risk register, which may be as simple as a spreadsheet or as complex as an integrated database using artificial intelligence for data completion and linking of information.

How is a risk register applied?

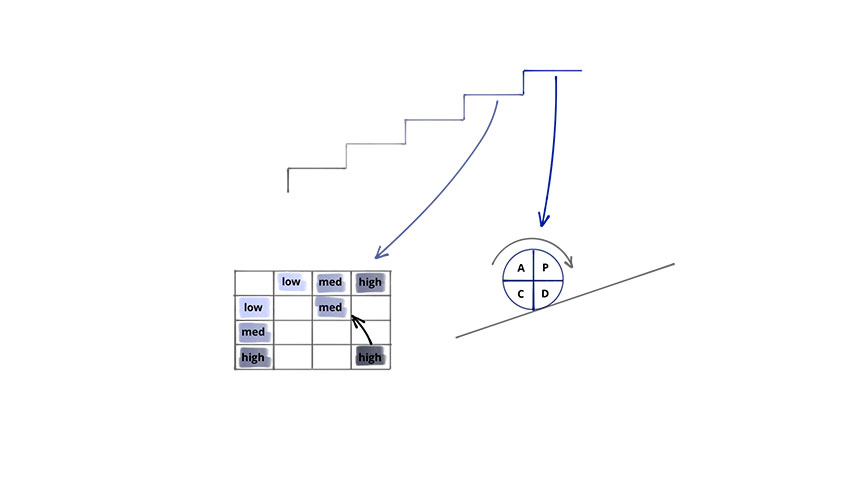

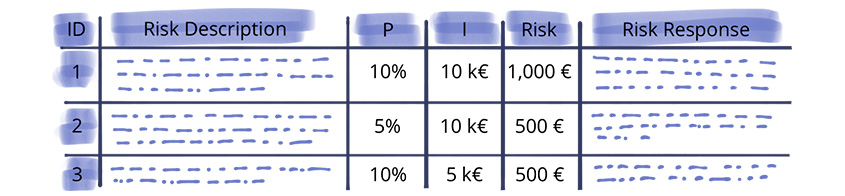

The simplest form of a risk register is a table listing all information required for risk management. The rows represent the individual risks while various pieces of information are organised in columns.

A basic set of risk information, i.e. columns in the risk register, are

- a continuous labelling for risk identification,

- an acurate description of the risk itself (i.e. what may happen and how does it affect the goals?)

- an estimation of the probability of occurrence,

- an evaluation of the impact and

- a proposal of a risk response.

There is much more information which may be included in a risk register, depending on the context.

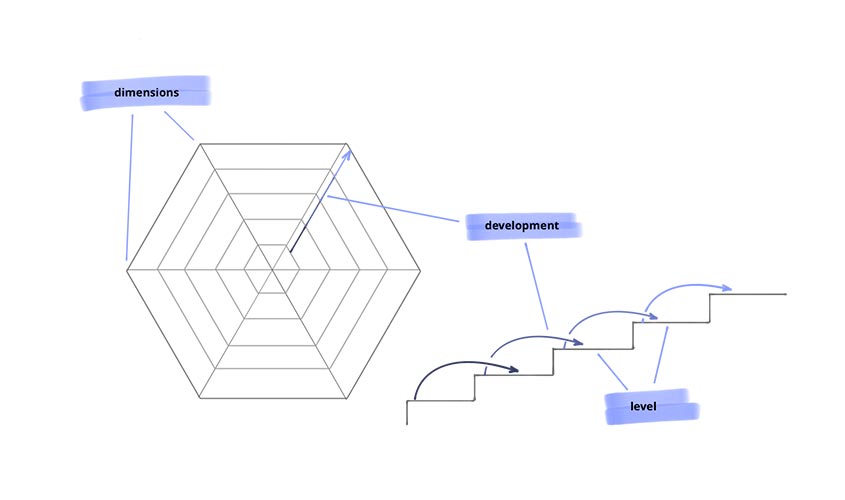

Two approaches lend themselves as blueprints for adding information to a risk register in the context of a risk analysis. The most convenient one is working row by row, i.e. identifying one risk and then adding all related information before going on with the next risk. This approach follows intuition and thus is easy to facilitate. However, it also results in rather lengthy workshops and is therefore tiring. Alternatively, you may want to focus on the risk identification and description first and add all other information later. This approach shortens risk analysis workshops but also required a much more disciplined facilitation.

Beware of pitfall!

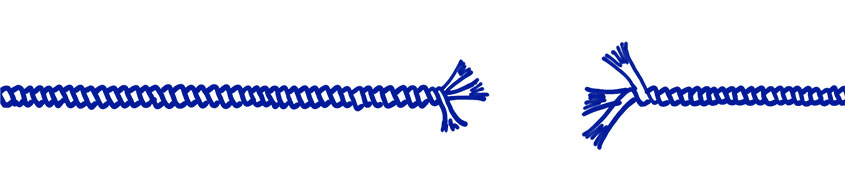

A risk register documents individual risks and their evaluation in a defined context. A common pitfall is to add up the individual risks and assume this number represents the overall product, project or organisational risk. Though this may be true in some rare instances, generally the actual product, project or organisational risk is significantly lower than the sum of the individual risks. The reason for this deviation between the overall risk and the sum of individual risks are dependencies between risks which are neglected if simply added up.

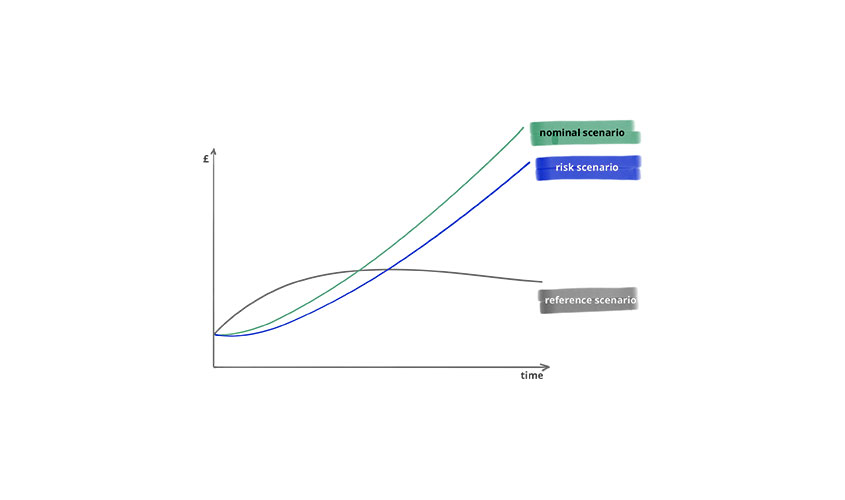

The transfer of risk information from one context to another is another topic to be aware of. Risk is defined as the “effect of uncertainty on objectives” (see ISO 31000:2018). Thus, if risks are transferred from one context to another, they need to be re-evaluated as generally the objectives shift with the context. Copy-paste of risk information from one risk register to risk register in a different context is simply wrong.

What is the use of a risk register?

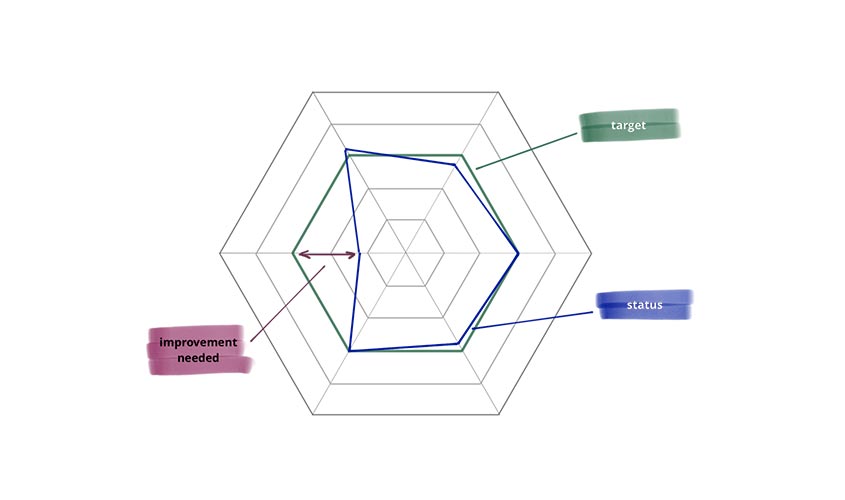

A risk register summarises all information on risks within a defined context. Thus, it provides all data required for an effective risk management for the product, project or organisation. It also documents risk management-related activities by capturing changes in the evaluation of risks or decisions how to respond to risks. Therefore, the risk register allows for a detailed overview of risks and how they are managed.

Follow us on LinkedIn to learn on a regular basis how you can make the most of management tools, so that you will stay one step ahead of your competitors.