It was Christine’s dream job: project manager for a large digitization project at an established, economically strong medium-sized company. She had the opportunity to fully contribute her experience, the pay and working conditions were attractive, the company offered perspectives beyond the project, and the position itself was a significant career advancement for her.

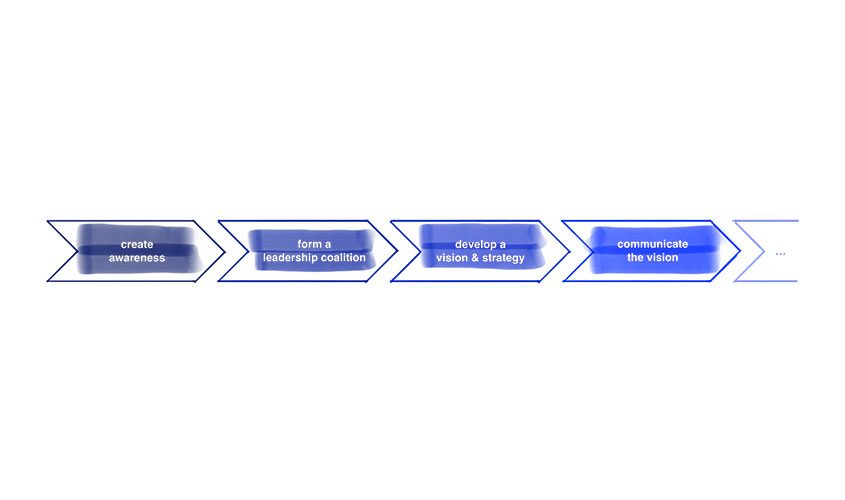

The first few months were unexpectedly tough. Even though the entire management officially supported the project and its goals, no one wanted to engage in the associated changes. But with her persistent nature and her skills as a change manager, she was eventually able to anchor the necessity of change and form a leadership team that truly supported the project. Christine’s second challenge now was to successfully implement the project.

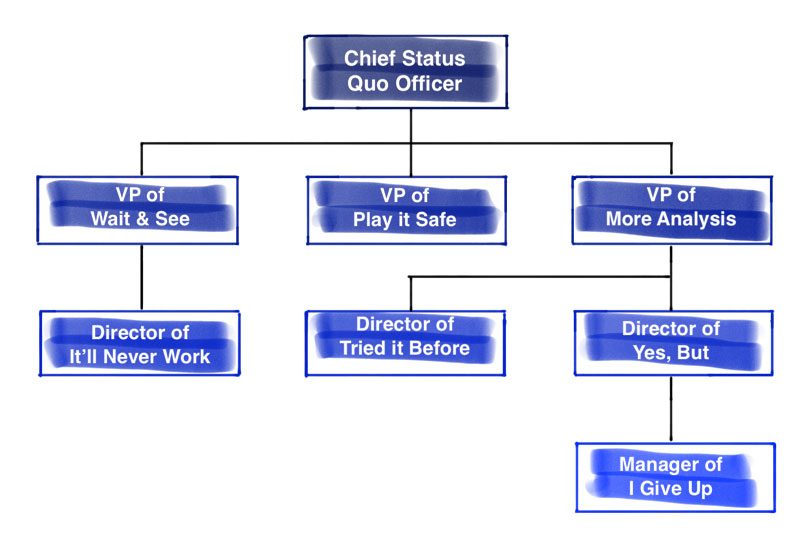

The power of status quo

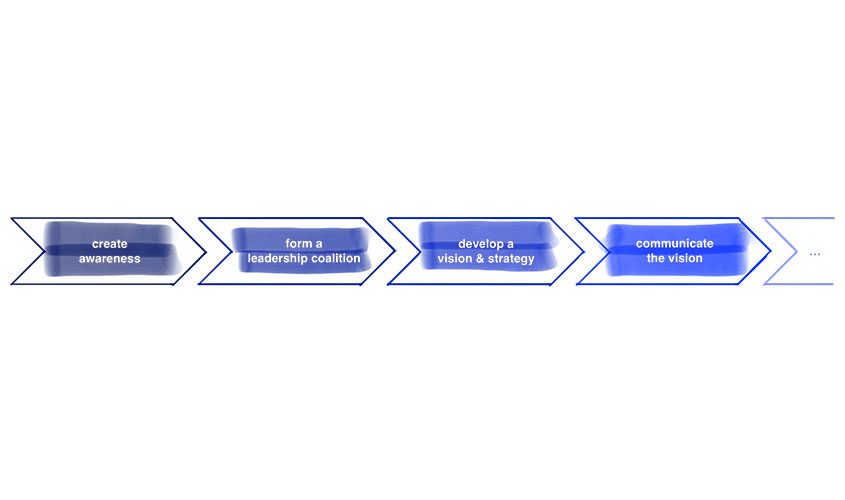

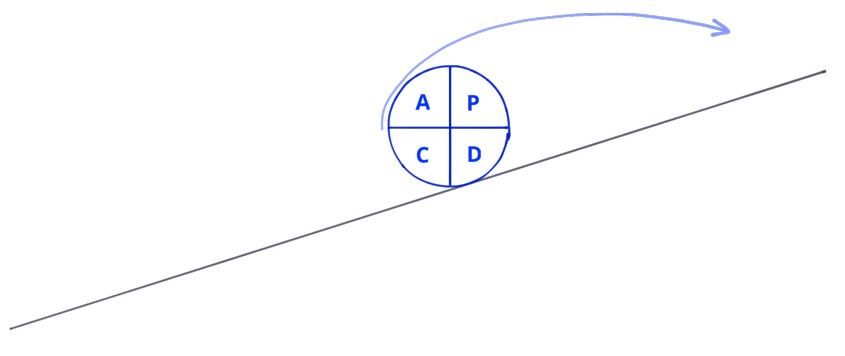

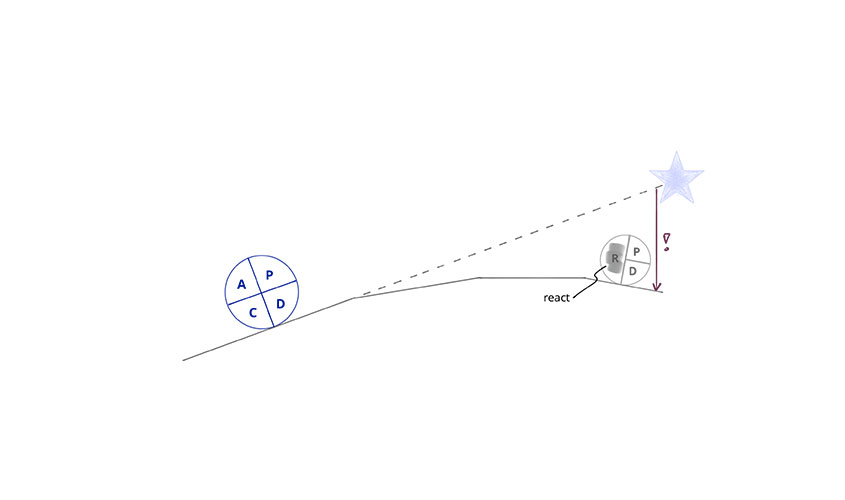

The first part of this mini-series showed what obstacles make the preparation of change processes difficult and how important decisions are made in the planning of changes that significantly influence later success. But even if “planning is half the battle,” implementation remains the second half that contributes just as much to the success – or failure – of a project.

When implementing changes, it is also about overcoming the power of the status quo and the inhibiting forces described in the first part of this series. Four elements can help you successfully master this challenge.

Preconditions for successful change

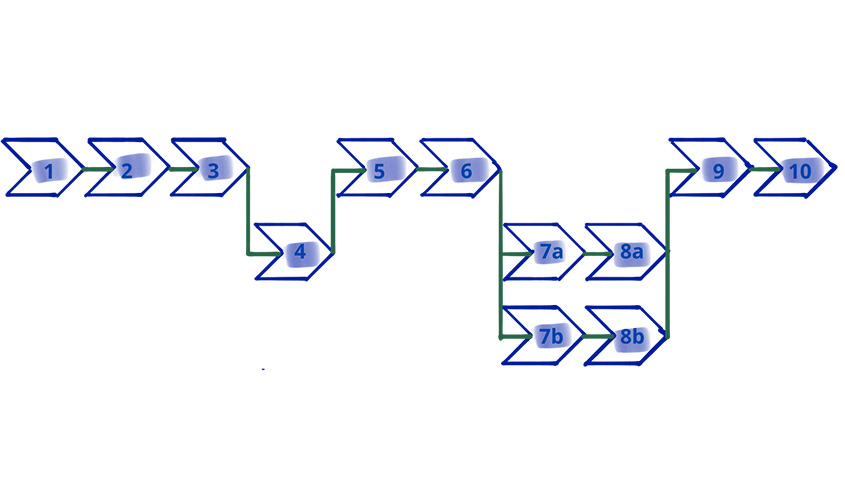

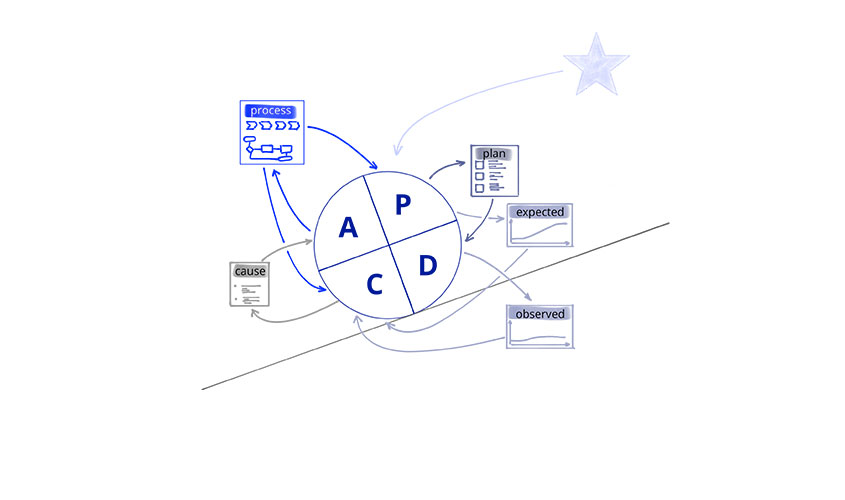

If you want to reap the fruits of success after a good preparation of your change project, you should show your stakeholders that your initiative is successful. At first glance, this may sound like a catch-22 situation, but it can be achieved through four simple elements.

Enable employees

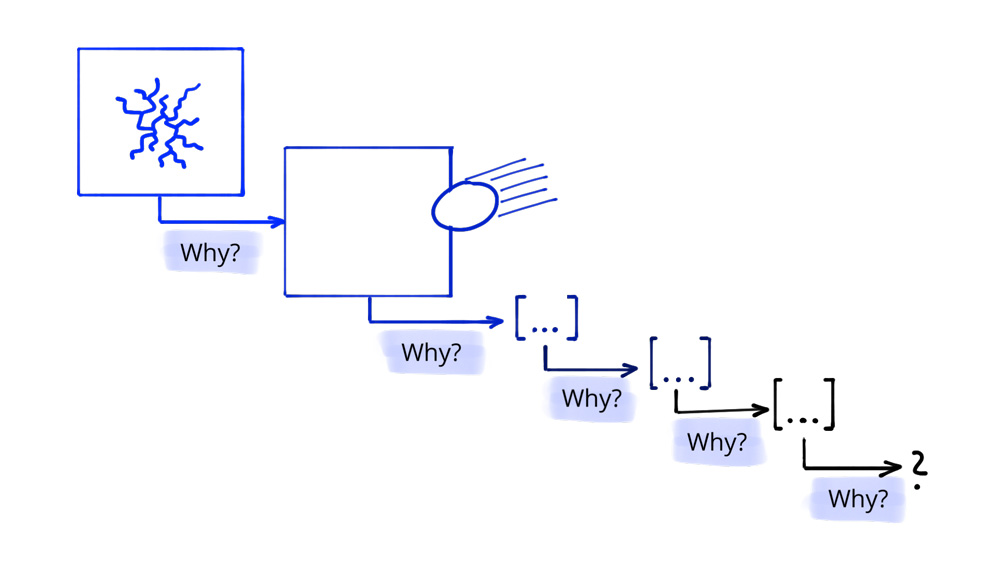

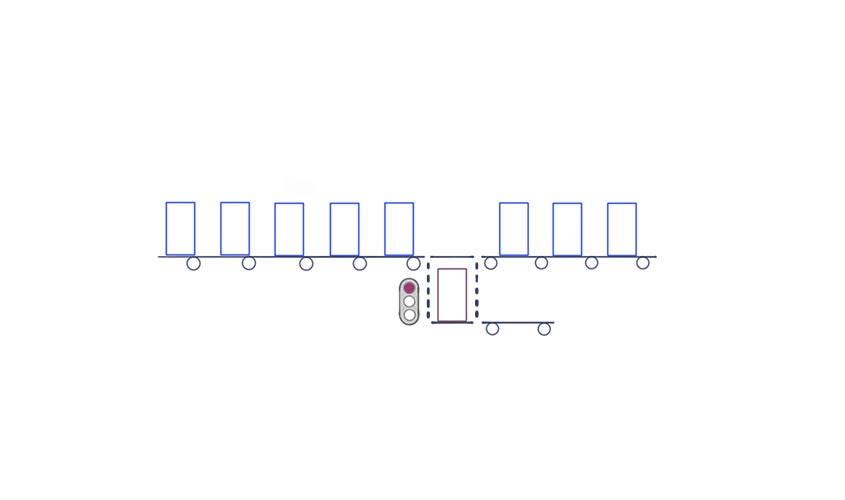

First and foremost, you need to ensure that your employees can act in line with your change project. In established companies, there are a multitude of defined processes and (partially unwritten) rules. These more or less fixed guidelines significantly determine how the company operates and functions.

Changes always mean that certain areas should be handled differently than before. This means that some of the existing guidelines need to be disregarded. However, this only works if you enable and encourage your employees to override existing norms and standards where necessary.

Generate quick wins

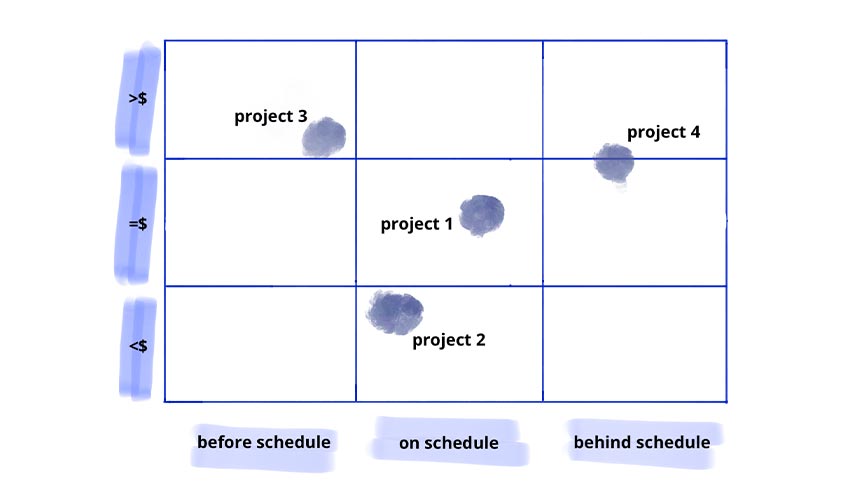

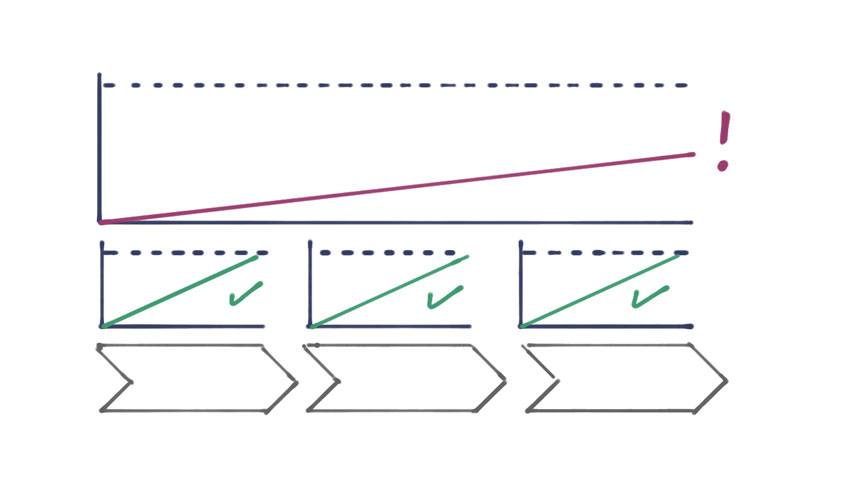

In most cases, a change project will not consist of a single measure, but rather a multitude of smaller steps. It is important to take the first relevant steps as quickly as possible.

This can demonstrate, on the one hand, that you are proactive and driving your initiative forward, and on the other hand, that you are heading in the right direction and your project is successful (despite any naysayers). If you can communicate early successes quickly, you solidify your position in the company and gain additional supporters who were initially skeptical of your project. This gives your project new momentum, which is essential for its further implementation.

Consolidate success and initiate further change

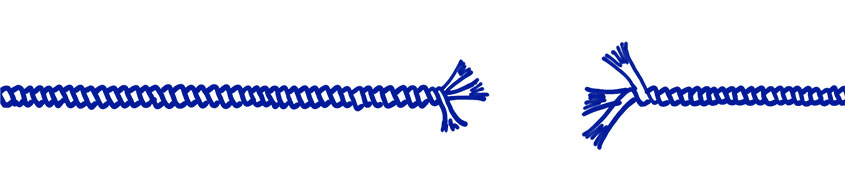

In addition to achieving early successes, it is critical to anchor the changes achieved sustainably in the organization. As just shown, achieving milestones leads to even hesitant employees supporting the project. However, if your organization quickly falls back into old habits, this is grist to the mill for those who would like to see the project fail.

At the same time, it is important not to rest on what has already been achieved, but to continue at the same pace and take further steps towards the stated goal.

Anchoring new behaviour

While at the beginning of a change project existing processes and rules need to be broken in order to enable change in the first place, at the end of the initiative it is necessary to establish and anchor new behaviors. Only in this way will the participants in the company also adhere to the new ways of working in the long term, and not fall back into previous patterns out of old habits.

If a company fulfills all four points in the implementation of change measures, it has a good chance of successfully completing the change project.

If you want to be successful in your next change project, contact us.