Especially in smaller companies, processes tend to become closely linked to those employees who are responsible for their execution. Over time, these employees have created their workflows according to their needs. The tasks along the process fit seamlessly into the daily workload, they exactly know what to do and the results are fine.

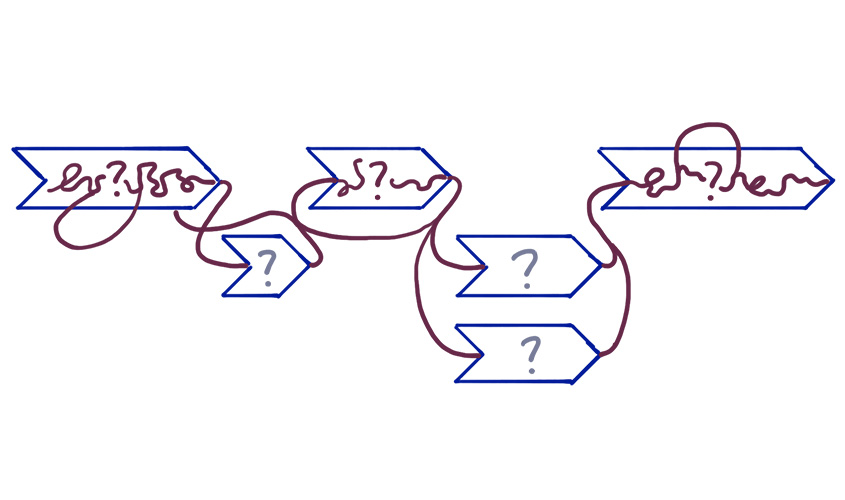

But when these employees quit their job, the new process owner faces the challenge to manage a grown and often not well documented process. Keeping the process functional is a tough task, and if external partners are involved in the workflow, complexity raises exponentially.

In such a situation, three steps help to ensure continuity and support optimisation of the process passed on to the new process owner.

1. Understand the Current Process Setup

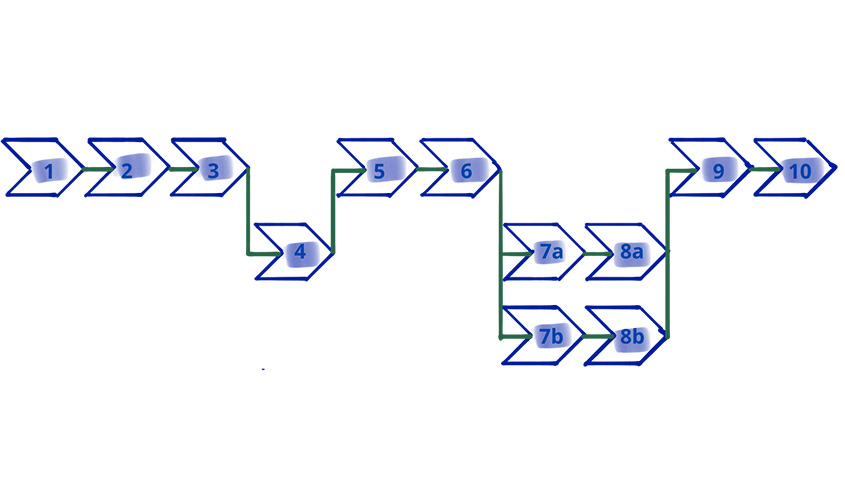

First, the new process owner should understand how the process is actually working. In this step it is helpful to visualise the flow of information and products with the support of all internal partners, e.g. in a value chain analysis.

It is helpful to include the former process owner in such an exercise as he has both the relevant process knowledge and the necessary experience. However, to avoid conflict, focus on recording the status quo and do not question the way things are as this will be taken as criticism by your predecessor. Rather, ask questions on how the process actually works and how the former process owner has contributed to its success. In this way you will pay tribute to the leaving employee and get an accurate picture of the process.

2. Internal Process Optimisation

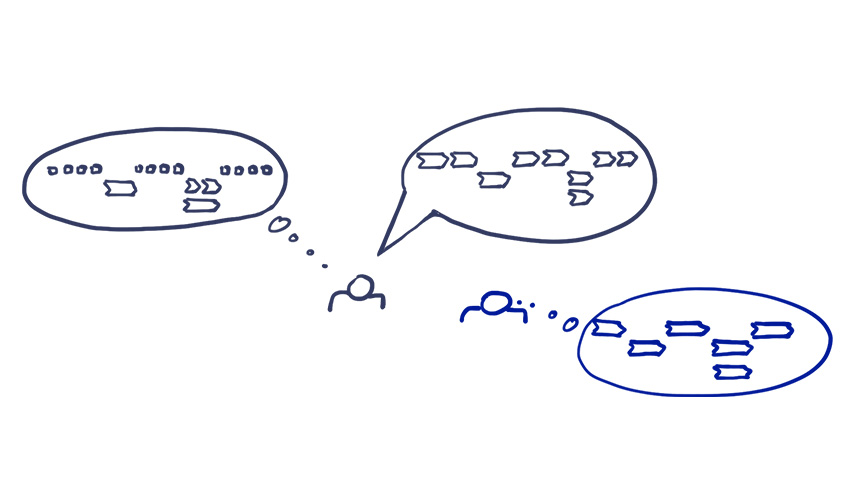

While you avoided questioning the status quo in the beginning, you should do exactly that in the next step, of course without the former process owner. The internal process optimisation is a task for the new process owner and should be supported by all internal process partners.

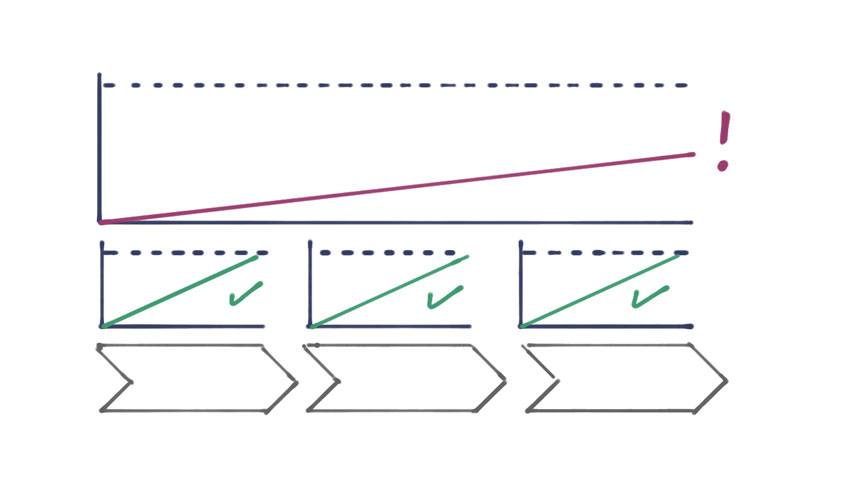

The optimisation should follow the procedure described in How to optimise internal business processes: Set the objectives, get to know the status quo (see Step 1), choose a suitable method, get the optimisation project done and integrate the improvements into existing structures. Besides, common pitfalls which unneccisarily slow down the process should be removed (see Three factors that slow down business processes)

3. Optimise External Interfaces

Finally, the interfaces with external partners should be improved. This step should be done as early as possible to avoid issues at the interfaces in the transition from the old to the new process owner. However, the internal processes should already be re-aligned before reaching out to externals.

The optimisation of external interfaces is best done in a workshop – either face-to-face or virtually. Within the workshop, a shared process understanding is established, interfaces are analysed, and weak spots are identified. An external facilitator with an unbiased view may support the process and mediate between partners if necessary.

It is important to create a positive atmosphere for the workshop where people feel appreciated to enable open and constructive feedback from all participants. Group dynamics need to be cared for from the beginning to avoid conflicts between individuals or groups. Here, different tools like a group exercise may be used to relax the atmosphere and create awareness for potential issues. Working with breakout groups, for example, allows for deep dives on selected interfaces.

The output of the external process optimisation should be an action list including all measures defined by all internal and external partners. Once implemented, these measures will help the partners involved in the process to contribute more efficiently and effectively to the process.

If you wish to know more about or need support with improving processes in a transition from one process owner to another, please get in touch with us and learn how we may support you.