Some years agoTom’s startup really made it: the online platform devised by him and his friends revolutionised the market. The trio’s strategy had paid off and within only three years their firm, having set off as a small living-room startup, had developed into a booming business with 15 employees, a turnout of hundreds of millions and a market share of over 30 percent.

But despite the seemingly positive figures Tom feels the pressure imposed by investors constantly growing and his position is becoming shaky. While revenues and his market share have lived up to his expectations, his company has still not been able to generate profits even though initial development expenditures and marketing costs were not higher than expected.

Tom is not the only person who has to fight these difficulties. According to an up-to-date study carried out by David J. Collis from Harvard Business School business strategies misfire because they fail to consider their whole strategic landscape. Young businesses and startups in particular founder regularly as they do no sufficiently take into account value capture and value realisation.

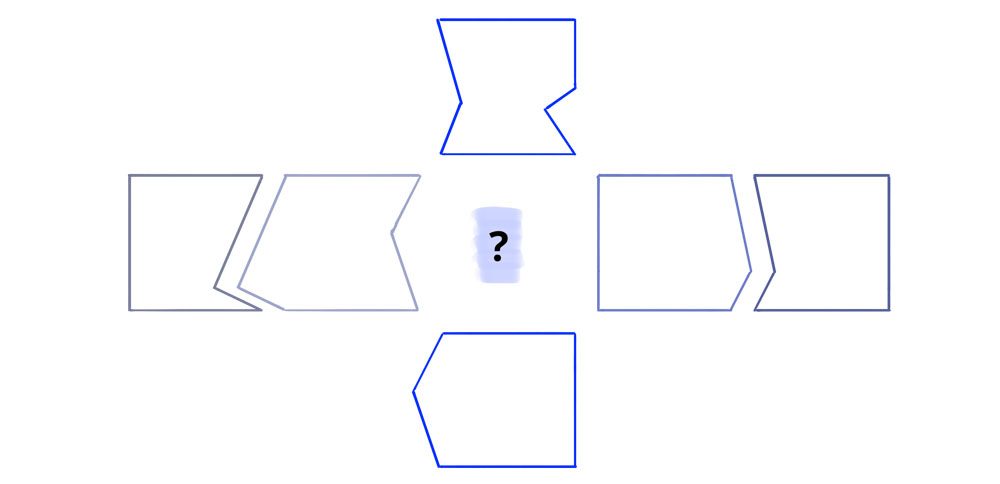

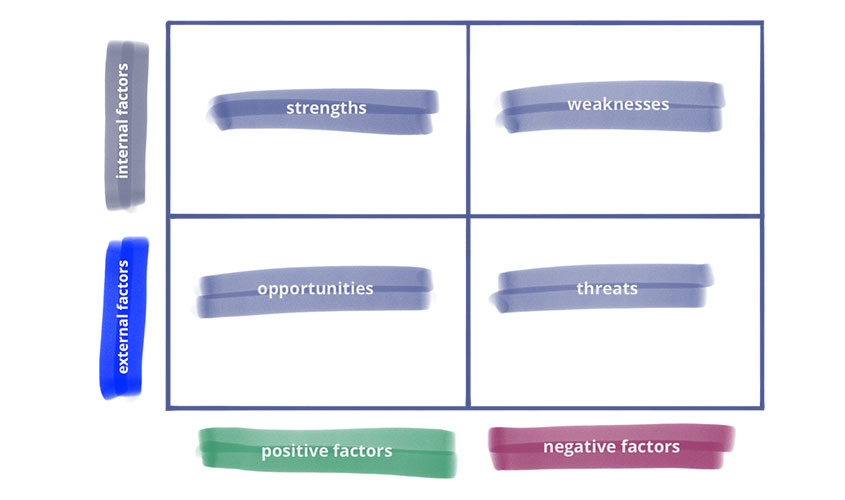

A company’s strategic landscape

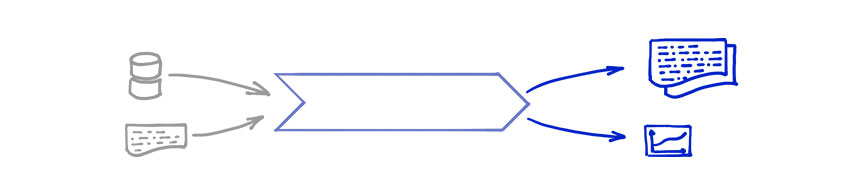

As was described in this mini series’ first part, a firm’s strategic landscape comprises business opportunities, the value potential of the respective business model, an enterprise’s value capture and value realisation and their final output.

For a business strategy to be successful, you need to look at all five of these areas, find a suitable answer that does justice to each of them and unhesitatingly translate them into consistent action. While, as was explained in my latest blog, established companies tend to lose track of changes in business opportunities, startups typically make mistakes in a different area of their strategic landscape.

Common mistakes committed by startups

The main strength of startups is that they address so-called hot topics and transform them into a novel business model, or that they fundamentally change the way customers’ needs are met. Naturally, this strategy concentrates on the first two components of their strategic landscape, i.e. business opportunities and value potential.

Yet, to go beyond business opportunities and attractive business models and to lead a company to long-term success, careful consideration should be given to the remaining three elements of a company’s strategic landscape. This is a standard weakness of young businesses and startups: They overestimate the opportunity of making profits in the new market, whereas they ignore the strong likelihood that competitors will eventually copy their ideas, or the young firm fails to build efficient structures and to develop necessary competences of staff.

What follows is, as with Tom and his friend’s firm, that these companies my be capable of creating considerable growth and amplify substantial market shares, but in the long run they will find it difficult to create attractive margins from their turnover and their gained market share.

Robust strategies for startups

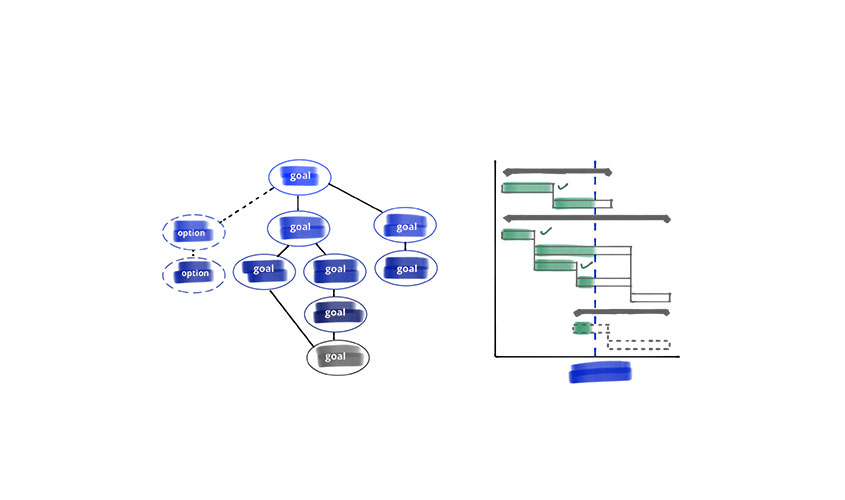

If you wish to develop a robust strategy, you have to field all aspects of a company’s strategic landscape. From the outset, startups ought to include questions of value capture and value realisation in their strategic planning.

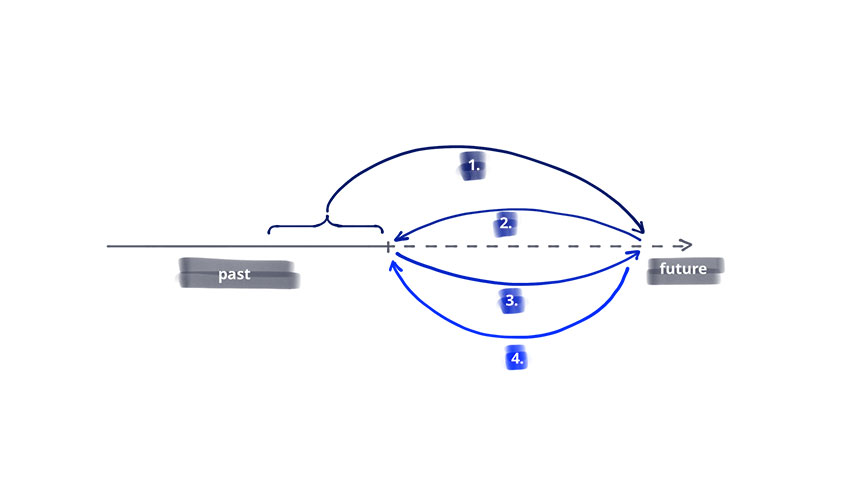

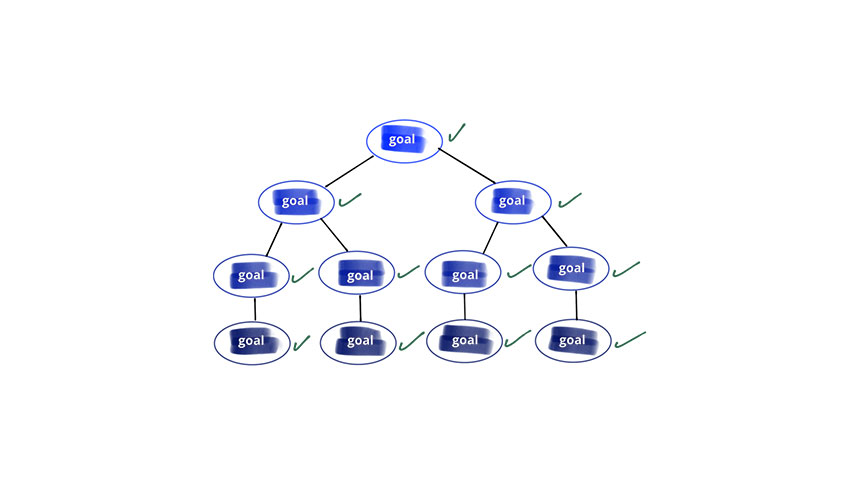

A good starting point is the following set of four questions:

- Will our business sector deliver decent profits?

- How will established companies react to our market launch?

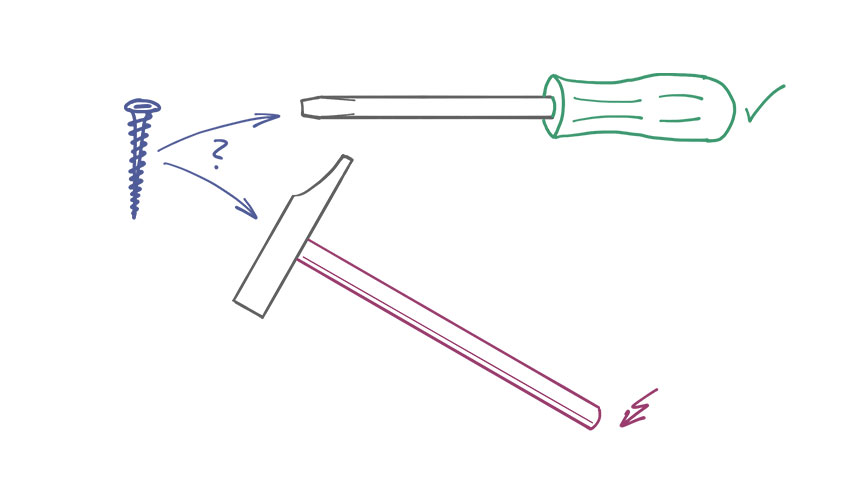

- How easily will our business model be imitated?

- How can a startup be scaled up efficiently?

The first question can reveal if a business concept or model should be put to the test in the first place. An attractive business concept with low profit potential (e.g. because the market is too small, necessary investment expenditures will be too high or expected margins too small) will not prove successful in the long run.

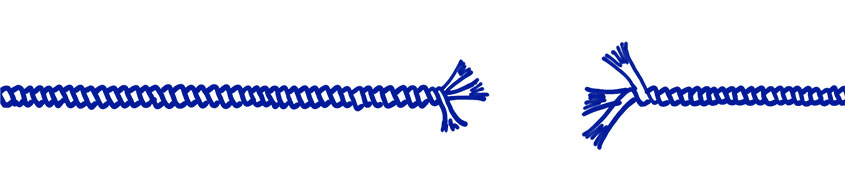

Questions 2 and 3 address the behaviour of competitors. In most cases an innovative startup enters an existing market in a new kind of way. But this also means that there are established companies unwilling to give up market shares. Sooner or later they will respond to the new competitor. Depending on how strong their market power is, they may severely hinder a startup’s market development.

When it comes to digital business models, you’ll have to check how easy it is to copy it. If its only innovation consists of not more than a few lines of code, it won’t take long until the idea is imitated. In such a scenario it will be unlikely for a company to gain both high market shares and high profit margins.

The last question examines the company’s future development. The characteristic agility and dynamic resilience embraced by many startups is a good precondition for generating new ideas and launching them into the market. For growth and profitability, however, other skills are required. Long-term success requires you to look ahead and provide, right from the start, the basis for developing structures and competences crucial for further expansion, even if you may not need them at the moment, and to implement this process of company growth early on.

If you wish to know how to combine all elements of your strategic landscape into a sustainable strategy, contact us for an informal free initial consultation.