On hearing “continuous improvement”, many people thing of the Deming circle or PDCA: plan an improvement, implement it (do), check the results and act upon the them. Once the cycle is completed, it starts anew and thus realises continuous improvement. The second thought, however, may probably be something like “But it’s not that easy!” or “The theory is fine – but it never works that way in real life!” – and considering all the failed initiatives to implement continuous improvement, these thoughts are understandable.

Nevertheless, PDCA is an effective tool to implement continuous improvement. As in many cases, the problem is that this instrument is applied in the wrong way: surveying failed process improvement projects, one comes to the conclusion that mostly the use of tools is responsible for their failure – and not the tools themselves.

Process optimisation as cause-and-effect chain

Process optimisation along the lines of PDCA basically follows the logic of a cause-and-effect chain. An existing process is deliberately modified (= cause) and as a result the efficiency or effectiveness of the process improves (= effect). This sounds trivial but, far from it, actually significantly impacts the approach to process optimisation.

Causal relationship between cause and effect

If process optimisation follows the logic of cause-and-effect chains, then there is a causal relationship between cause and effect. This relationship is created by the process which is to be improved and the interfaces with other processes.

Generally, these causal relationships are not just linear dependencies but form complex networks. These networks are normally not limited to the process to be improved but linked to other processes and activities by interfaces.

Explicability of the effect

Another consequence of process improvement as a cause-and-effect chain is that you can explain the effect of any process modification. Causal relationship provides a rational explanation why a certain effect results from a given cause.

The rational explanation may be used in two ways. If the causal network is known, the effect of any modification can be predicted. Likewise, if both cause and effect are known, the causal network can be reconstructed.

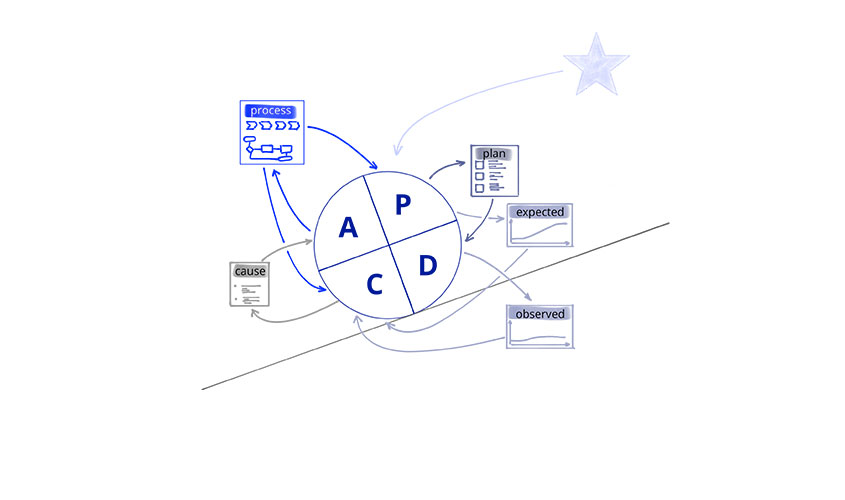

Optimising causal networks based on PDCA

Given the implications of process optimization as a cause-and-effect chain, PDCA is ideal for continuous improvement. In this context, the respective steps are:

Start

Before first applying PDCA, the optimization target needs to be defined (see „How to optimise internal business processes“ [Link: https://rno-consulting.com/en/how-to-optimise-internal-business-processes/]). The target should be clearly defined and quantified whenever possible.

Plan

Based on the current understanding of the process, i.e. its causal network, an optimisation step is worked out which modifies to process depending on the defined target. Having done so, both the necessary measure (= cause) and the expected outcome (= effect) have to be described.

Do

The described step is implemented, with a constant monitoring of the resulting effects on the process.

Check

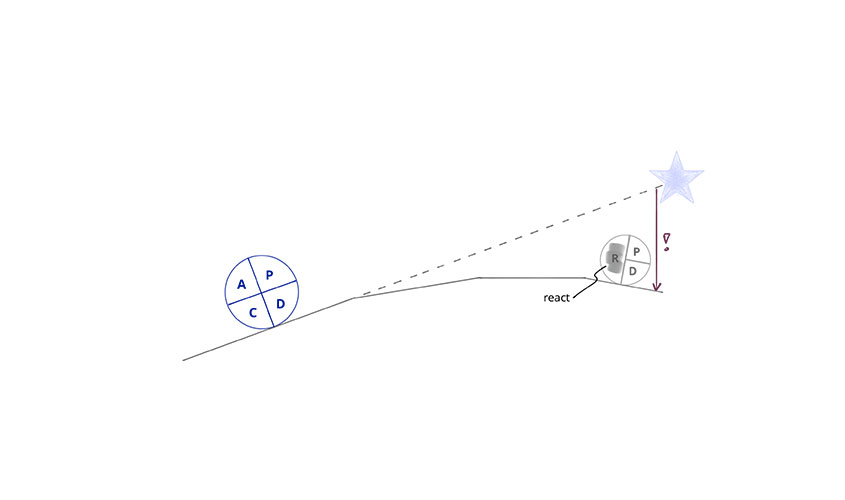

Once the optimisation step is implemented, the actual effects are compared with the expected ones. If the observed results match those expected in the plan-step, the PDCA iteration is completed. In case the overall target is met, the optimisation cycle is completed, otherwise another iteration begins (i.e. plan).

If the observed results were not expected, the current process knowledge needs to be adjusted. To allow for such an adjustment, it is essential to understand why the implemented change resulted in the observed effect.

Act

Once the causal relationship between the implemented measure and the observed effect is established, the knowledge about the process needs to be updated accordingly. The updated knowledge will then serve as a basis for another PDCA iteration.

Benefits from PDCA process optimisation

Using PDCA for process optimisation requires thorough application, which may prove difficult in busy day-to-day operations. Most of all, the analysis of unexpected effects is readily skipped in favour of quickly implemented fixes.

However, by sticking to the steps described above, you will win twice: First, you will achieve the set targets for process improvements. Second, your knowledge about relevant processes will increase.