The pressure is on, and Mike’s post of CEO is threatened: Over the past ten years he has been constantly strengthening the market position of his company and continuously improving all areas within the enterprise. On the whole, all had been going well and the business owners had always been more than satisfied with his achievements.

However, for about two years business figures have been moving in the wrong direction: first sideways and then downhill, the downward trend having become more and more obvious lately. His strategy no longer worked although Mike had started several counter-initiatives and implemented as planned. Why was it that a weathered strategy that had been used and approved of for years suddenly flopped?

The answer is simple and does not only hold true for Mike’s company but in almost any cases where strategies do not render the desired results: The strategy misfired because it failed to take into account the whole strategic landscape of the business. Mike has made a mistake which according to a current study by David J. Collis is rather common among established companies.

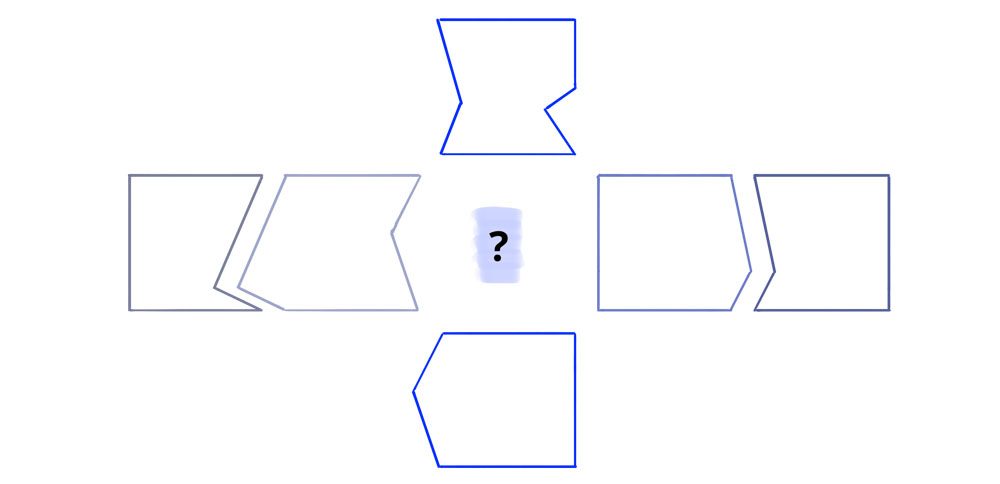

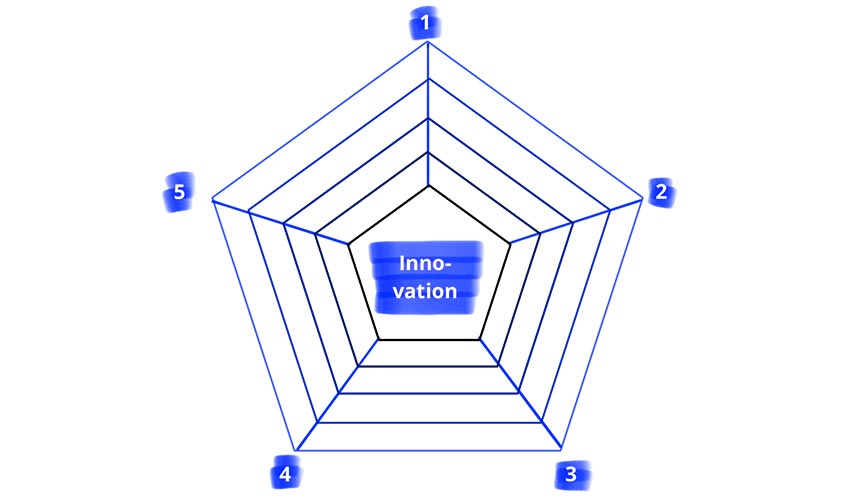

The strategic landscape

A company’s strategic landscape is characterised by five elements: set of opportunities, value-creation potential, value capture, value realisation and business performance. A successful strategy has answers and approaches that harmonise these five areas reasonably well.

Set of opportunities

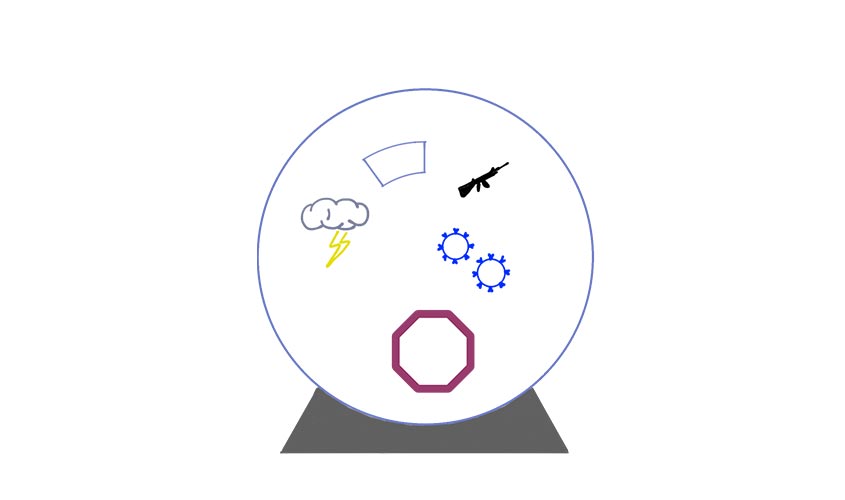

The set of opportunities describes the external environment of the respective company. They comprise, among other things, the political and legal framework or technological developments, but also demographic trends or changes in our natural environment.

These opportunities define the frame within which values can be captured – plus what is to be seen as “value”. This frame will change over time, thus causing answers given and approaches chosen to be adapted to these altering general conditions. A useful tool to take into account these changing conditions is scenario planning.

Value-creation potential

A company’s value-creation potential depends on the chosen business model: How can a company, based on current and future opportunities, generate value for potential customers? What payment models are chosen for products and services?

This sector of the strategic landscape has the potential to transform whole industries, as was the case when video shops were supplanted by streaming services or when pay-per-call contracts were replaced by flatrate phone call offers.

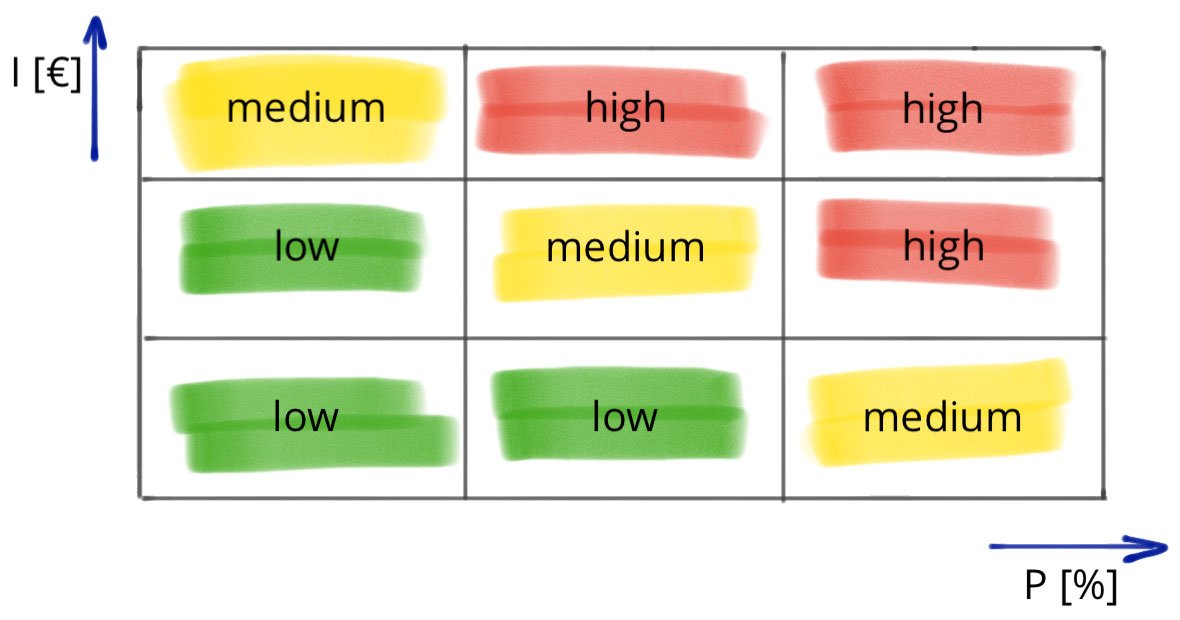

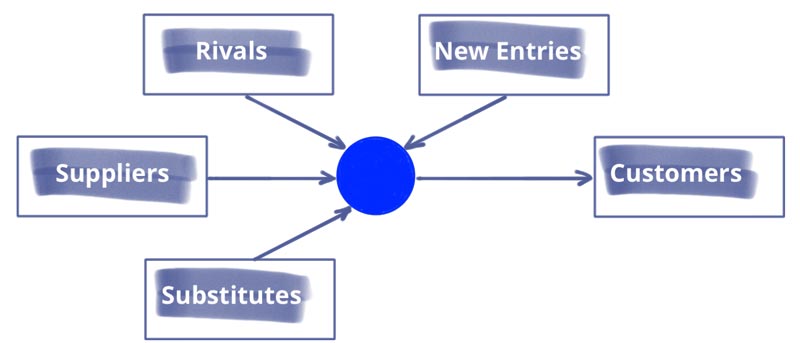

Value capture

While the business model describes what creates value for potential customers, value capture is about how this value for the company can be measured. Here topics like market attractiveness, the best positioning of one’s own company or possible reactions of competitors have to be assessed and taken into account.

All these questions can be tackled with classic strategic approaches, like positioning, Michael Porter’s five forces model or SWOT analyses. An unorthodox, but interesting way of designing a strong strategy is to make use of game theory.

Value realisation

Value realisation comprises anything generally called strategy implementation. It intends to build capabilities and resources needed for long-term success and to re-adjust structures, so that they be more adaptable to change.

Having identified suitable and necessary measures, questions of timing and deadlines need to be taken into consideration. In this way the respective organisation can be guided into adopting a new strategy without straining its capacities.

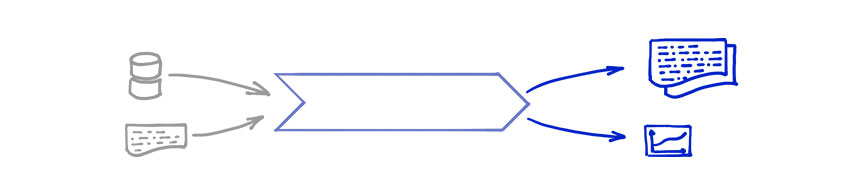

Business performance

The fifth feature of the strategic landscape is represented by the actual outcome. Often within the scope of controlling, here current developments are observed and compared with intended targets, objectives and goals. If necessary, corrective measures are being implemented.

However, measuring performance must not be the end of a process chain, but merely a single building block of a company’s strategy.

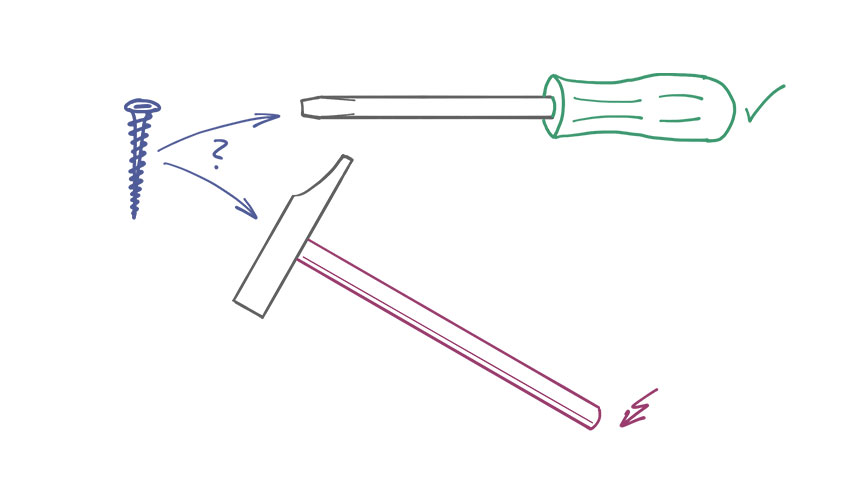

A common mistake of established companies

A robust and successful strategy equally takes into account all five components of the strategic landscape. Established companies, like Mike’s in the introductory example, often make the mistake of focussing too much on value capture, while at the same time they tend to neglect changes in opportunities and to overlook new value-creation potential.

Often these enterprises have for years been successful in one specific business model and have made themselves at home there. Turnout and profits have been stable or are even increasing, so there seems to be no reason to change the running system.

When things have become a habit, change is frequently seen as unnecessary: “We’ve always done it this way – and it always worked!” is what you will hear all too often. But this approach will only work on the condition that the external environment will basically stay the same or that no competitor will start to satisfy customers’ demands in a different, more effective way.

When external conditions will change after all, CEOs like Mike more often than not seek to make up for a worsening outcome with new or better answers in the area of value capture and value realisation. It is all too clear, though, that this will prove unsuccessful in the long run.

Robust strategies for incumbent companies

A robust strategy which can be successfully implemented is holistic, i.e. when it comes to planning and implementation, it takes into account all five elements of the strategic landscape. Established companies in particular have to keep analysing their set of opportunities and value-creation potential and not only to pay attention to pursing a specific business model.

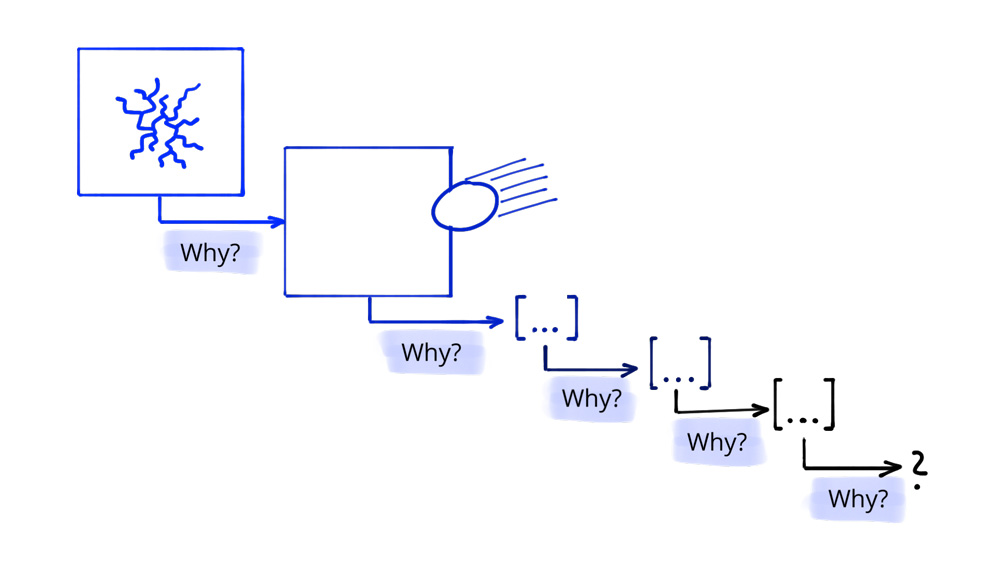

A first step can be questioning the way things have always been done:

- How is the environment of my business currently changing?

- Are customer demands changing as a result as well?

- What new approaches are there to satisfy customer demands?

- What do these changes mean for the business model I have adopted?

This reactive approach helps companies realise when it is necessary to adjust their business model. In this way enterprises can be prevented from clutching to outworn business models and, as the proverb has it, beating a dead horse.

Better still would be a pro-active approach that anticipates future developments and predicts customer needs and business models not having yet been identified. This is how enterprises can say goodbye to outdated strategies and business models while there is still time and also actively shape the market, hence strengthening their own market position.

Contact us when you want to lead your company into the future with an active strategy.