Management tools are a dime a dozen. And yet, contrary to popular belief, most of them are good and helpful if used correctly and in an adequately defined context.

In “Tool Box Talks” we introduce you to common and less well-known tools and show you how you can exploit their potential for your enterprise, with today’s focus on the PDCA-Cycle.

What is the PDCA Cycle and when should it be used?

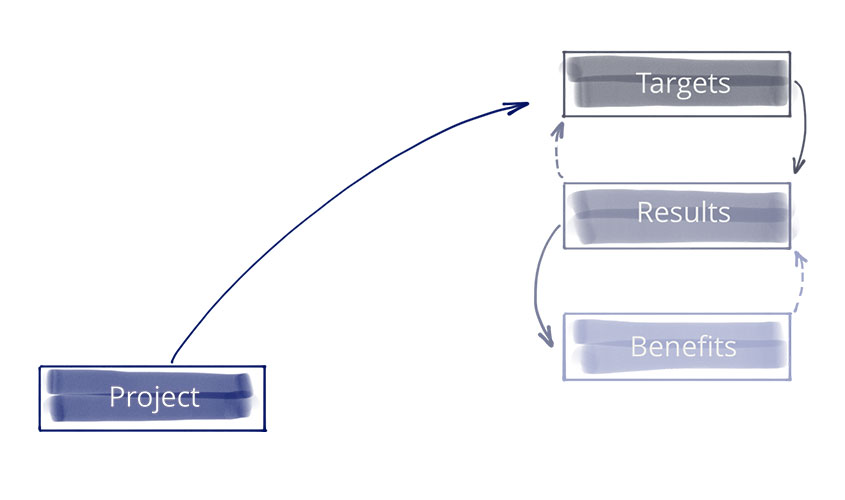

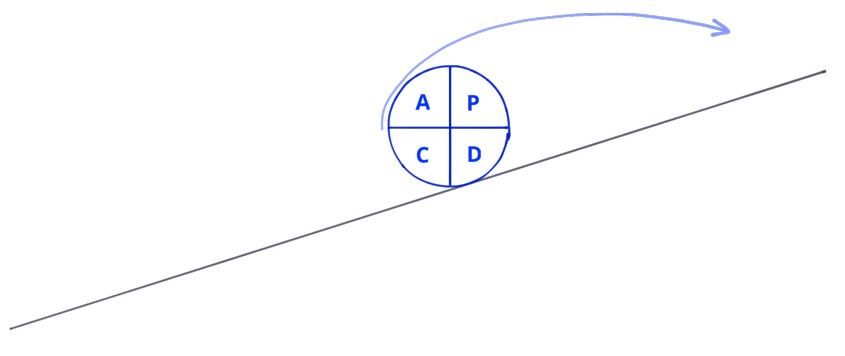

The PDCA Cycle, also called Deming Cycle or, after his inventor Walter A. Shewhart, Shewhart Cycle, is a process and quality improvement tool. It helps to systematically enhance internal procedures and practices by constantly checking in what way an adaptation of processes leads to different results.

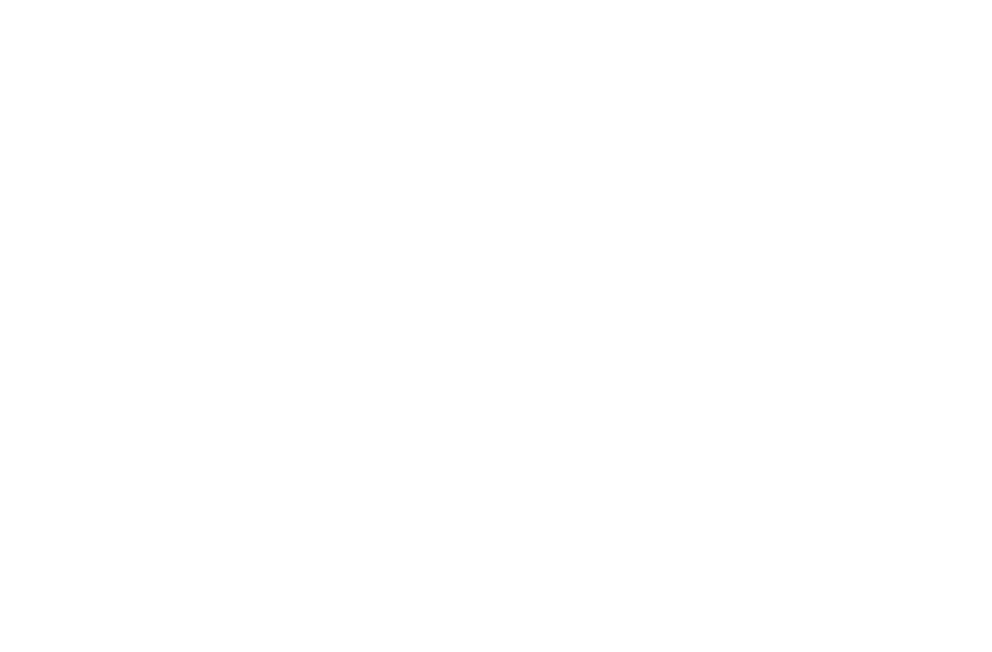

The PDCA Cycle starts with the initial state of affairs, which is to be improved in a first step of improvement, with more to follow. This approach implies that processes are gradually improved and it unsuitable for designing processes from scratch or fundamentally changing them. What is more, the PDCA Cycle presupposes a cause-and-effect relationship between adapting processes and measurable changes of results. So before you apply this method, you should know well what the causal connections of the process in question are.

How is the PDCA Cycle used?

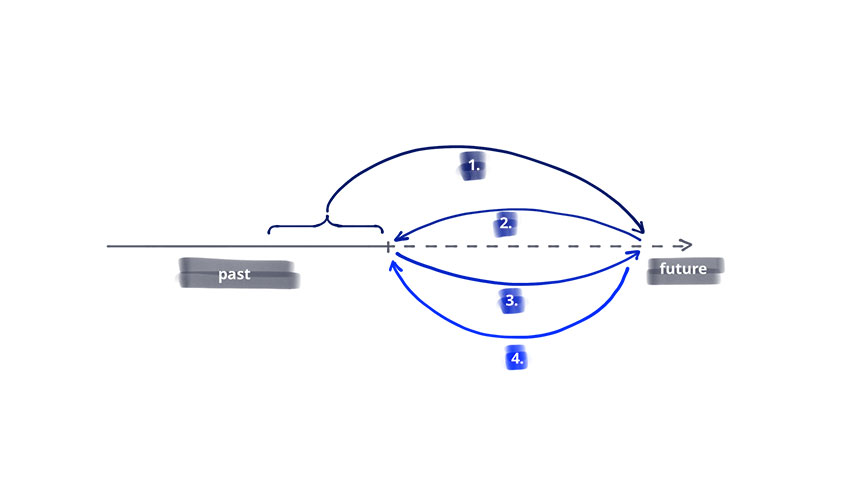

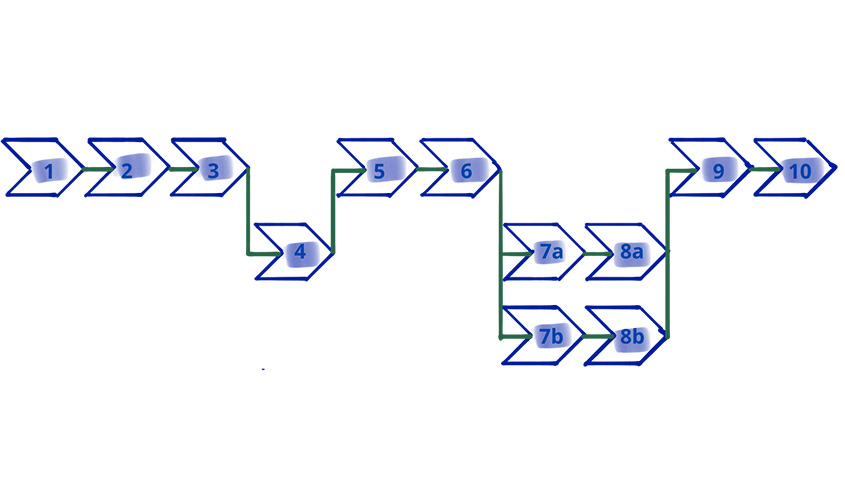

To reach a certain aim when using the PDCA Cycle to improve processes, you do this in four steps (cf. “How continuous improvement may succeed“):

- Plan

- Do

- Check

- Act

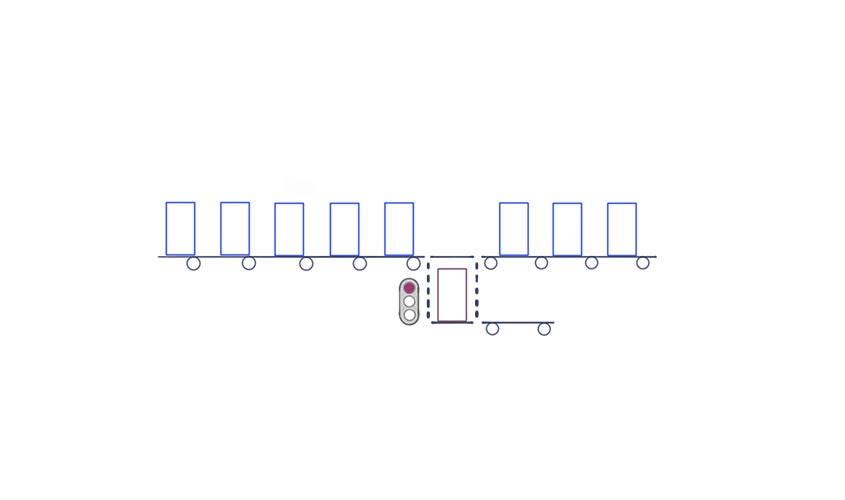

The first stage (“Plan”) defines what modification the process is to undergo and what will be the result expected from this adaption. The consequent implementation (“Do”) puts the planned measures into effect. If you use a special testing environment because, say, you want to protect running internal processes from unforeseen side-effects of your measure, you make sure that your testing environment diplays the real conditions in your company, so that you will be able to apply your insights to running processes.

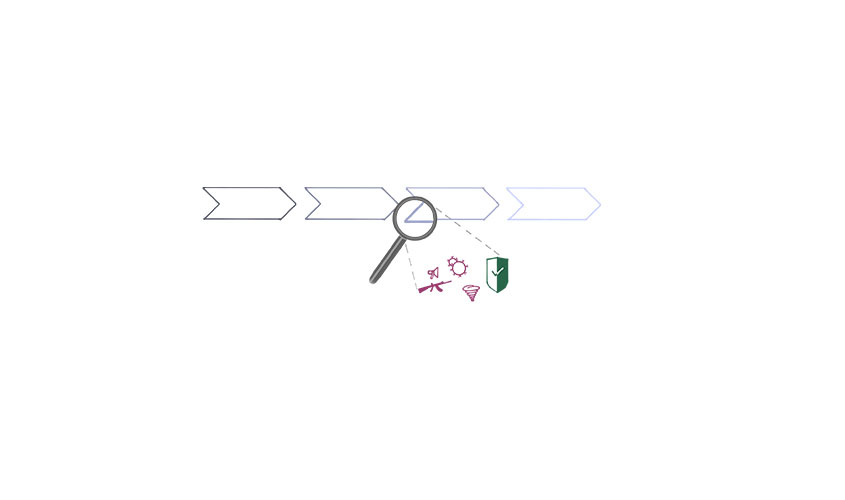

In the third phase (“Check”) you compare the observed results of process adaptation with your expectations. Especially if the results do not match your predictions, you’ll have to find out why the measure diverges from your assumptions. Finally (“Act”) you update your knowledge about the relevant process and its documentation.

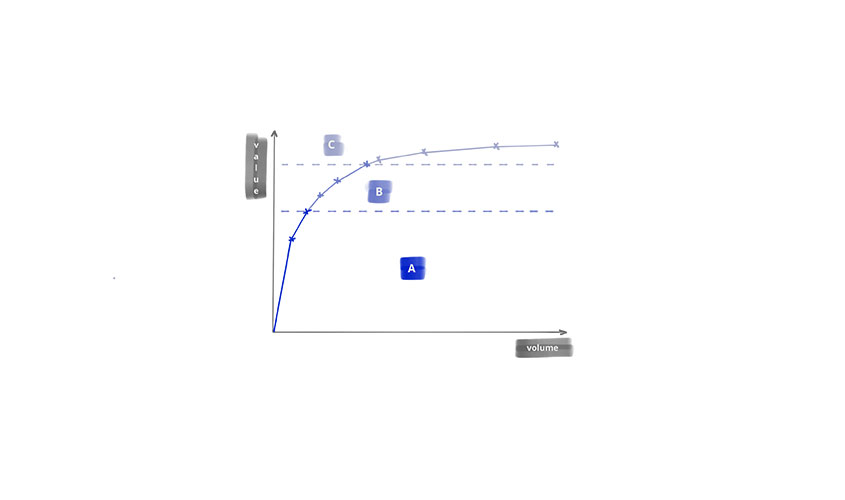

To reach the initially defined objective of optimisation, the PDCA Cycle is applied not once but several times until the final aim is reached, with each iteration gradually improving the process or the knowledge about it.

Avoiding the pitfall

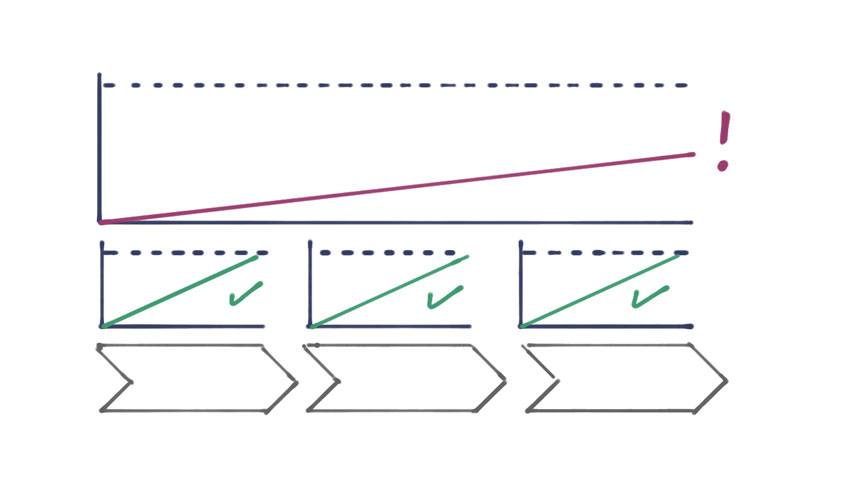

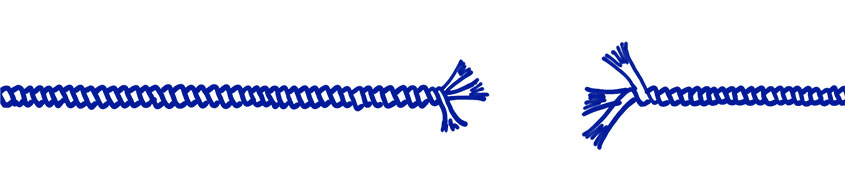

Most customers find it easy to plan and implement an optimising measure. However, instead of checking the result (C), adapting the knowledge of the process (A) and planning a new strategy for improvement on this basis (P), in many cases the only response is a new set of activities – downgrading PDCA to PDR (plan-do-react).

The reasons for this behaviour range from a lack of measurable exptations to a loose work ethic. The result is always the same: The well-thought-out methodology of the PDCA Cycle is interrupted and rather than gradually improving processes, they fall victim to a blind testing of random measures. If processes should be improved despite the odds, they are so by mere accident, not by a systematic approach that follows clear guidelines. What you want to achieve, however, is a predictable and sustainable improvement.

What use does the PDCA Cycle have?

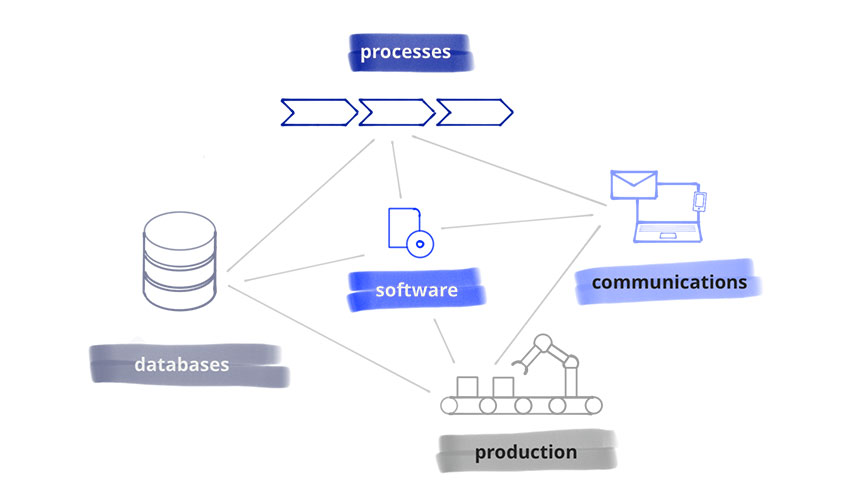

If used consistently, the PDCA Cycle will have a double benefit: for one thing, it ensures permanent gradual improvement of processes to which it is applied; for another, it leads to a precise understanding of the process and the way it relates to other internal processes as the current knowledge about the process is constantly reviewed and adapted if need be.

Follow us on Xing and LinkedIn to learn on a regular basis how you can make the most of management tools, so that you will stay one step ahead of your competitors.